Bernard Trink, the brash, unforgettable “Night Owl”, spent decades chronicling Bangkok’s seedy red-light boom. His fearless column shaped the city’s global image, scandalised critics, thrilled readers—and left behind a legacy of coded wit and neon-soaked lore.

We reflect on the life and legacy of one of the most remarkable foreigners to have lived in Thailand over the past sixty years. His name was Bernard Trink. An American by birth, he was brash, controversial, and politically incorrect—even by the more forgiving standards of his era. Trink made his name chronicling Bangkok’s notorious nightlife, a world that, beginning in the 1960s, helped shape the city’s image as both provocative and mysterious. It is a reputation the city retains to this day, drawing millions of visitors each year. More than just a columnist, Trink helped create a world and lifestyle that has attracted generations of foreigners, many admittedly for all the wrong reasons. Yet his legacy endures—not just among those who were scandalised by what he represented, but more enduringly among those who remember the thrill, colour, and excitement of the memories he helped bring to life.

Bernard Trink, one of the most recognisable foreign figures in Bangkok’s modern history, died in October 2020 aged 89. For decades, he was the trusted chronicler of Bangkok’s red-light nightlife. His column, Night Owl, ran for 37 years. It first appeared in the Bangkok World and later in the Bangkok Post.

He will always be remembered for his unique voice and fearless reporting. Trink documented the comings and goings of Bangkok’s go-go bars, sex dens, and massage parlours.

These flourished through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, right up to the early 2000s. His writing helped shape Bangkok’s global image as the capital of sex tourism.

How a young American veteran found his calling covering Bangkok’s seedy glamour in the swinging 1960s

Born in New York in 1931, Bernard Trink first came to Bangkok in 1952. He was serving with the US armed forces during the Korean War. His time in Asia sparked a lifelong interest in the region. After the war, he worked as a journalist in India, Hong Kong, and Japan.

He returned to Bangkok in 1962 and taught English at several universities. However, a stroke of luck in 1966 changed everything. He was offered a job as entertainment editor at the Bangkok World. That opportunity marked the beginning of a career that would define him.

In a 2014 interview with Barbara Woolsey of Coconuts Bangkok, Trink recalled how it all began. “The guy didn’t know what he was doing,” he said of his predecessor. “I didn’t know about entertainment either, but I was resolved I was going to find out.”

That resolve made all the difference. Trink dove headfirst into the vibrant nightlife scene exploding around him. New bars were opening every week. Bangkok’s entertainment zones were growing at a frenetic pace. Trink was everywhere, taking notes and giving publicity.

Trink became the go-to name for press attention as nightlife hotspots scrambled to make their mark

Almost daily, he received invitations to bar openings, cabarets, and massage parlours. Many venues were owned by American GIs in partnership with Thai wives. Trink gave them the oxygen of press attention. He was seen as the stamp of approval for new nightlife hotspots.

Initially, the Night Owl column stretched across three pages. It featured his musings, gossip, and signature “trinkisms” — coded phrases only seasoned readers understood. Most Fridays, readers found photos of scantily clad hostesses, jokes, and sarcastic social commentary.

His language was original, punchy, and often risqué. Trink wrote in a style that no other journalist dared to copy. By the 1970s, his column was not just a Bangkok fixture — it became known globally.

During that time, Western tabloid editors picked up on Trink’s lurid yet engaging reports. His column, full of shocking detail and playful innuendo, provided the perfect material. Consequently, Bangkok’s reputation as a sex capital was reinforced. The city’s “anything goes” image was born.

At the same time, Night Owl became essential reading for thousands of foreigners. Whether serving in the military or passing through as tourists, many readers started their weekend with Trink’s column. It was their guide to the city’s hidden side.

Despite his subject matter, Trink remained sober, reserved, and critical of much of what he reported on

Despite writing about drinking, drugs, and debauchery, Trink himself remained a teetotaller. He didn’t drink alcohol and rarely stayed out late. Ironically, he was also critical of prostitution. He often warned Western men not to fall in love with bar girls.

Time and again, he called for more rights for women. He also condemned violence in relationships. Nevertheless, Trink remained fascinated by the demimonde — a term he coined to describe the shadowy nightlife world.

“I don’t give a hoot,” he often wrote. That closing line became his trademark. It reflected a cynical but consistent detachment from the stories he reported. Trink covered the highs and lows without apology.

However, not everyone appreciated his work. As the AIDS crisis spread in the 1990s, criticism of the sex industry grew louder. Trink’s column, which many viewed as celebrating that world, became controversial.

Earlier, in the mid-1980s, a key turning point had already come. The Bangkok Post later purchased the Bangkok World. Afterwards, the Night Owl column was cut from three pages to one. Photos were banned. Trink’s visual presence, once featured with bar girls and punters, was removed entirely.

Tighter editorial control in the 1990s finally brought the Night Owl column to an abrupt and silent end

Editors began enforcing stricter guidelines. They insisted on more “family-friendly” content. Trink’s flamboyant commentary was increasingly trimmed or censored. Still, he refused to be silenced.

Throughout the 1990s, Trink survived repeated attempts to shut the column down. One major effort to axe it triggered a backlash. Loyal fans launched a letter-writing campaign to save Night Owl. They succeeded, but only partially. The column was reduced to half a page.

Eventually, in December 2003, a new editor pulled the plug. There was no warning. No farewell column. Just silence. Trink’s last words were left hanging in mid-sentence, unspoken.

Even so, the Bangkok Post retained him. He stayed on as a book and film reviewer. Though less glamorous, it allowed him to keep writing. He reviewed regularly from his cluttered desk, still using a manual Olympia typewriter.

By that time, Trink had also undermined himself. He publicly voiced a controversial theory that HIV did not cause AIDS. The claim drew fierce criticism and damaged his reputation. It gave ammunition to those already pushing for his removal.

Trink’s iconic style and signature phrases secured his cult status among visitors and long-time residents

Nevertheless, Trink’s impact on the city and its foreign community endured. Visitors and residents alike continued to speak of the Night Owl. His writing style, full of indirect references and coded meanings, stayed with them.

One long-time visitor recalled how, even decades later, he would always look for the Night Owl column on arrival in Bangkok. For him and many others, Trink was the man who knew everything. He had the inside story, every time.

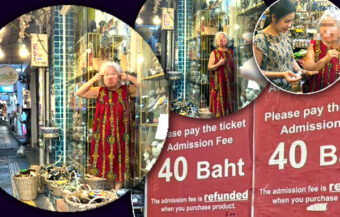

In person, Trink was instantly recognisable. He wore oversized suspenders and chest-level trousers. He always buttoned his shirts to the top. Around his neck hung a large owl medallion. A Filipino bar owner had given it to him years before.

He could be spotted in Patpong, Nana Plaza, or Soi Cowboy — the very places he covered. Often, he was scribbling notes or chatting with regulars. His appearance never changed. His presence never faded.

Trink also coined the term “Soi Cowboy” to describe one of the city’s now-famous nightlife areas. But perhaps his most enduring phrase is “TIT” — “This is Thailand.” The acronym captured the confusion, charm, and contradictions of life in the Kingdom.

Trink’s legacy lives on through phrases and memories shared by those who knew Bangkok at its wildest

To this day, “TIT” remains in wide use. Foreigners use it online and in conversation. It sums up their love for Thailand despite — or perhaps because of — its mysteries.

Bernard Trink died on Tuesday, 6 October 2020, at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Reports say he succumbed to a blood infection. He was survived by his devoted wife Aree, a son and a daughter.

Jim Thompson the original ‘farang’ who ushered in the heyday of the expat in 20th-century Thailand

US serviceman’s son’s search for his Dad’s Thai girlfriend from 1968-1971 comes to an abrupt halt

His death marked the end of a remarkable life. It also signalled the closing chapter of a golden era for Bangkok’s expats. Trink was more than just a writer. He was a voice, a symbol, and a witness to history.

As long as foreigners walk through Soi Cowboy, Patpong, or Nana, Trink’s name will echo in the neon lights. His trinkisms, his medallion, and his “hootless” attitude will certainly not be forgotten.

To thousands, he was not just a journalist. He was the guide through Bangkok’s nightlife labyrinth. He watched it rise, and he chronicled its changes.

Indeed, it was a hoot. Thank you, Bernard.

Join the Thai News forum, follow Thai Examiner on Facebook here

Receive all our stories as they come out on Telegram here

Follow Thai Examiner here

Further reading:

Jim Thompson the original ‘farang’ who ushered in the heyday of the expat in 20th century Thailand

‘The Serpent’ serial killer who terrorised Bangkok released by Nepal on human rights grounds

Iconic 70s Bangkok comes to life again as the dark story of The Serpent wows world Netflix audiences

Filming of Fast and Furious movie begins in Krabi in what will be a big boost to the local economy